Image sourced from Classical Pearls. Available at here

An In-Depth Interview with Heiner Fruehauf

A while ago Heiner Fruehauf, PhD, LAc sat down with his student and colleague, Bob Quinn, DAOM, LAc to discuss the finer points of “Brain Gu” Syndrome, specifically as it pertains to the treatment of Lyme Disease. This discussion is best understood as a follow-up to and elaboration of the ideas presented in Heiner and Quinn’s earlier interview about Gu Syndrome published in the Fall of 2008. This interview has been updated with the inclusion of The New Heritage Formula Series of Herbal Products by Classical Pearls.

QUINN: Welcome Heiner. It is nice to sit and have a cup of tea with you to discuss one of the most perplexing health conditions of this time, Lyme disease. I wanted to start by establishing your own experience in this area.

HEINER: I have been seeing Lyme patients since the time I started my practice, more than 20 years ago. At first I wasn’t aware of what I was treating. I was differentiating symptoms and tried to devise a traditional diagnosis that fit the overall picture as closely as possible. I see this conversation as a follow- up to our earlier discussion on Gu Syndrome. After many years of treating Lyme disease with Chinese herbs, I can say with great certainty that, from a classical Chinese perspective, Lyme is a specific type of Gu Syndrome that I have labeled Brain Gu.

In Western terms, Brain Gu incorporates a wide range of nervous system diseases that are associated with a host of tortuous symptoms, and that in most cases are hard to diagnose: Lyme disease, which is associated with the specific pathogen borrelia burgdorferi; co- infections of Lyme, i.e. babesiosis (piroplasmosis, texas cattle fever, tick fever), bartonellosis (cat scratch disease, trench fever, Carrion’s disease), ehrlichiosis (tick fever), anaplasmosis, rickettsiosis (Rocky Mountain spotted fever, certain types of typhus), tick-borne encephalitis (TBE), tularemia (Pahvant Valley plague, rabbit fever); and other chronic nervous system infections most often transmitted by the bites of ticks, mosquitoes, flees, lice, and spiders.

The most obvious ancient Chinese equivalent to these types of modern Brain Gu infections is malaria. The word Nüe 瘧 (“malaria”) is often mentioned in the Chinese medical classics alongside Gu syndrome. It literally means “torture disease.” Just like there are hundreds of types of spirochetes that can potentially cause the variegated syndromes now commonly synthesized under the term Lyme disease, many different types of Nüe syndrome were recorded in ancient texts. In addition to the viral and spirochetal pathogens mentioned above, they encompass a broad range of nervous system afflictions endemic to the jungle regions of Southeast Asia, such as malaria, Dengue fever, and leptospirosis. The West Nile virus also belongs to this class of pathogens. In addition, many mystery syndromes such as Morgellon’s disease can potentially be associated with Brain Gu.

In modern medicine, there is a common misunderstanding about the nature of these pathogens. Most physicians believe that they are highly localized, for example in a distant region dominated by swamps or jungles. They are viewed as contained—as something that doesn’t spread uncontrollably beyond its point of origin. Infection is therefore thought to be rare, caused by the highly unlikely scenario of being bitten by an exotic animal that transmits a bizarre parasite. It is my personal experience, however, that infection by pathogenic agents inflaming the nervous system represents one of the biggest epidemics of our time. I am basing this sweeping statement on 30 years of observing patients who suffer from severe and debilitating symptoms—and yet have been diagnosed by the regular medical system as having “nothing.” Lyme and its co-infections make up about 30 percent of my current practice. Most likely, a variety of different factors such as global warming, progressive weakening of the blood-brain barrier due to growing EMF and RF exposure, and chronically depressed immune systems may be the cause of this phenomenon.

I would like to ask my fellow practitioners in the natural medicine community to be on the lookout for these patients. Don’t be afraid of long treatment times and symptom pictures that make little sense from a traditional perspective. Chinese medicine has real answers for these patients, and it is an opportunity to work with this unusual yet not uncommon syndrome. However, it is important not to revert back to common herbal prescriptions for fatigue and anxiety/depression learned in school, such as Liujunzi Tang or Guipi Tang or Xiaoyao San—in Brain Gu patients, you won’t make much headway with these. The average TCM practitioner tends to refer this type of patient to an MD, chiropractor or naturopathic physician, most often because of a perceived lack of solutions for this complex and high-maintenance disease. The Gu classics of Chinese medicine, however, offer the most sophisticated and clinically useful solutions for Lyme and Lyme-like infections of the nervous system that are available to us today. In treating Lyme, we need to mimic the behavior of the pathogen itself: be able to adapt to ever changing symptom pictures, and stay ahead of the spirochete’s ability to camouflage and transform itself, by constantly changing the details of our prescription within an overall anti-Gu and pro- terrain approach. This is the method the Gu classics convey, and what I see lacking in most modern treatment plans.

At the same time, it is important to know that the treatment of this condition is not as complex as it may appear. I have spent much time synthesizing the ancient Gu teachings into a modular approach that can be implemented by modern practitioners. First of all, we need to recognize that Lyme disease patients always present with 1) pathogenic influences (spirochetal infection or, in Chinese terms, fengnüe: “torturous wind” invasion), and 2) deficiencies on all levels, which opened the door to the infection in the first place. Every successful approach to the treatment of Lyme needs to have multiple building blocks that can be combined in flexible ways, and that address both of these deficiency and excess aspects of this disease. In addition, we and our patients need to be prepared to administer treatment over a long period of time. Otherwise, the terrain cannot be restored and the parasitic load will not be reduced in a lasting manner. My goal, therefore, is to share a treatment approach to Lyme that is backed by historic depth and age- old clinical experience. At the same time, I will outline a series of herbal building blocks that can be combined in modular fashion, and which are simple enough to learn that they can be safely prescribed in Western TCM clinics.

Before we get there, it is important to emphasize that both practitioner and patient need to be prepared to ride what I have called “the rollercoaster.” Even in the best-case scenario, these patients will be like the proverbial canary in the coal mine for a long time. Even if you manage to get symptomatic relief right away, there will come the inevitable solar flare, or atmospheric pressure change, or individual stress, causing things to dip again for a while. For most Lyme patients, two steps forward and one step back—and plateauing in between—are the normal form of progression on the road towards recovery.

In many Lyme patients, moreover, not too many pathological changes can be detected in the blood. Their internal organs often have not deteriorated enough to register suspicious values in standard tests. The brain and the spinal medulla, however, are affected from the onset. Tick induced viruses and spirochetes love to hide in nerve tissue and create their mischief there. Due to the protective function of the blood-brain barrier, our immune system has only limited access to the brain, and thus has a particularly difficult time fighting pathogens in this area. Lyme patients thus often have intense cognitive and neurological symptoms, but according to their blood work it appears that there is nothing wrong with them.

The degenerative process initiated by Lyme is either so “stealth” that it can’t be detected, or happens to make its home in a place where it can’t be found. Due to the general lack of medical validation this type of person faces, Lyme patients suffer not only from the tremendous physical and emotional pain associated with this disease, but also from the fact that their doctors and even their family members often believe they are crazy. The people closest to them may say: “I don’t know what to do with her anymore. She doesn’t have anything wrong with her, but she doesn’t want to work. She is so volatile emotionally. She has completely changed”. The attitude reflected in these kinds of comments represent the ultimate torture for Lyme patients. There are lots of chronically inflamed people out there who have never been diagnosed appropriately. As Chinese medical practitioners, it would be inappropriate for us to send them away. We should work with these patients, and encourage them throughout their arduous healing process: “Yes, it will take a long time, but there are solutions; time honored solutions that Chinese medicine has to offer.”

QUINN: In this interview, we want to get into the specifics of which herbs you have had clinical success with and also provide some nuts and bolts information for the treatment of Lyme disease. But, before we get into this, I would like to ask a little bit more about the component of cognitive dysfunction or shen disturbance in patients with Lyme disease. Can you talk a little about treating this shen component of Lyme before we tackle the specifics of herbal treatment?

HEINER: I think we owe these patients a great deal of gratitude. As I mentioned already, they are the canaries in the coalmine of our time. Currently, our nervous systems are being challenged more than at any other time in the history of humankind. Lyme patients are registering things that we all feel. For most of us, however, our nervous systems are strong enough to withstand the higher pitch of vibration that comes with modern lifestyle and all the unprecedented magnetic and environmental disturbances we are experiencing on the planet right now. Recent clusters of solar flares, earthquakes, tsunamis, tornados and forest fires are all natural signs of a heightened state of tension in the environment. This uptick in energetic intensity takes a toll on everybody’s nervous system, but is experienced as violent and anxiety provoking by most Lyme patients.

In my own clinical practice, I have observed that the one symptom most patients have in common, whether they suffer from Lyme or not, is anxiety. Even if they don’t acknowledge it, they are suspended in a constant state of restlessness and jitteriness; a fear that something terrible is going to happen; that they are not in control; or that there is always one more thing they need to do. Lyme diseased patients who display the shen disturbance you described are, in a certain sense, magnifying this high pitch intensity that we are all affected by in one way or another. In other words, modern industrialized people, myself included, are all shen disturbed to a certain degree. When you go into remote areas where people still live in a tribal or nomadic way, where people are still living in communion with nature and are completely present, you can see immediately that their eyes are completely different from ours, so much more open and clear. The eyes are, of course, the key to diagnosing shen disturbance in Chinese medicine.

I have seen people like these recognize shen disturbance in the modern travelers who happen

to pass by their tents. Often, they feel sorry for us. “Why do you have all this fear in your eyes,” they wonder. As practitioners, we need to remember this condition when we become disturbed or afraid of a Lyme patient. Rather than questioning the sanity of the patient, or categorizing Lyme suffering as deserved karmic retribution, we should let these cases serve as an extreme mirror for ourselves and the society we live in. In patients like this, the shen may be disturbed, but underneath there is most often a “fuxie”, a wind pathogen that has invaded the body, digging itself deeper and deeper through the six layers until it has reached the shaoyin layer. At this depth, it affects the heart and the kidneys. The marrow of the spine and the brain traditionally belong to this deepest layer of the body. This is where it is the hardest to detect a pathogen and where it will cause the greatest damage.

The biggest challenge with Lyme is not so much that there is a shen disturbance, or that it may be difficult to treat from a standard TCM perspective. The most difficult thing is the “syphilitic” aspect of the patient’s psyche, which is most often expressed by a gaping feeling of hopelessness. Most Lyme patients have an underlying voice in their head that seems to say, “I have already invested 15 years in the process of getting better; it didn’t work,” and perhaps, “I will prove that your treatment will not work, either.” In a certain way, this mentality is part of the disease. Even my front desk personal has become skilled in recognizing patients suffering from Lyme or other forms of Brain Gu—they are invariably individuals that have a higher degree of doubt, ask a lot of questions, and thus require a higher degree of maintenance. They are the ones that tend to call your clinic shortly after an appointment, saying “I took only the tiniest dose of the herbs and experienced an explosion of symptoms. I feel worse now. I don’t think this is going to work.” This sort of inner angst is a common feature in Lyme patients.

Continuous education is therefore very important for Brain Gu patients. Their sense of hopelessness and the belief that nothing is going to work must gradually be transformed. While this happens, you need to hold the patient’s hand for 3-5 years, and in some cases even longer. This is how long it realistically takes to reduce the presence of Lyme to levels that the immune system can handle. Our work is done when the remaining spirochetes, if there are any left, are like lichen on a tree. Lichen doesn’t generally suffocate a tree, and the tree is able to thrive despite the presence of lichen, moss, mushrooms, bugs, and other organism that have chosen to make the tree their home. Furthermore, the patient’s immune system must be supported until there are no more autoimmune reactions; in other words, until the body is confident that it is back in control and won’t be overwhelmed by the scary invaders. This process will take a long time.

If the infection is recent and the patient is younger, it may take three years. Otherwise, it will take five years or even longer, especially if the condition has been going on for decades and the person is extremely deficient to begin with. However, during this time the rollercoaster will gradually be climbing upwards—much better than the overall downward spiral they experienced before.

Moving on to the more specific discussion of traditional anti-Lyme herbs and formulas, I will start by outlining the primary herbal categories I recommend on the basis of classical medical texts for the treatment of Lyme disease:

The first and most important category for a traditional Brain Gu remedy consists of herbs that expel the “wind” we have been talking about. The Neijing emphasizes how the shengren, the sage and superior doctor, “takes great care to avoid wind influences like deadly arrows.” It is clear that the wind diseases and even the shanghan (cold injury) disorders featured so prominently in the Neijing and Shanghan lun (Disorders Caused by Cold) are not limited to variations and sequelae of the common cold and arthritis, as often believed. They include the Lyme related jungle fever syndromes I keep mentioning. Diseases that are classified as “wind” in Chinese medicine exhibit a multitude of signature symptoms, i.e. a fluish and malaised feeling accompanied by a pronounced aversion to drafts and varying degrees of wandering pain in the head, neck, back and extremities. Most Lyme disease patients suffer from these symptoms. The Chinese concept of wind, moreover, generally implies a pathogenic attack from an outside source. One Chinese character for disease (ji 疾) literally depicts a person struck by an arrow, a graphic image for the phenomenon of external wind invasion. Lyme and other “wind torture” diseases most often enter the body through the bites of insect and other animals.

To treat Lyme-like diseases, the Gu classics therefore outline an approach that incorporates herbs with wind-dispelling effect—a relatively novel concept, since most of us have been conditioned to use wind-dispelling herbs only for acute disorders and for short periods of time. The first and most important category of traditional brain Gu treatment, therefore, does not feature botanicals considered to be directly anti-parasitic, such as Qinghao. It offers herbs that disperse wind, and at the same time limit damage to the patient’s source qi, thus making them suitable for long term use. These herbs should further be combined with “internal herbs,” such as anti-parasitic qi tonics, blood tonics, and yin tonics. This pairing will make them even safer for long-term use.

The next set of categories consists of anti-parasitic and immune-modulating herbs that are generally considered to be tonic, particularly for the damaged blood, qi, and yin aspects of the body. I have discussed these categories at length in previous interviews and articles on the general treatment of Gu syndrome. The blood and yin tonic categories are of particular interest in the treatment of Lyme.

There is also a category of herbs for body pain, which is another common symptom for Lyme patients. In this category, you have Xuduan (Dipsacus), which is often used as a Lyme treatment in the form of Teasel root tincture by naturopaths. I particularly like to use Wujiapi (Acanthopanax) for spirochetes. I also use Shenjincao (Lycopodium) and Duzhong (Eucommia) for arthritic body pain.

Another category of herbs addresses the notorious biofilm, a slimy matrix in which micro-organisms tend to embed themselves. This self-produced barrier enables the pathogens to evade attack by the immune system, and escape the noxious effect of anti-parasitic substances. This protective film is difficult to break open, transform, or expel. The ancient Chinese approach to Brain Gu pathogens appears to have accounted for this ohenomenon, since Gu Formulas regularly contain aromatic herbs that move qi and blood and are simultaneously anti-parasitic, such as Sanleng (Sparganium), Ezhu (Zedoria), Yujin (Curcuma) and Zelan (Lycopus).

In addition, the earthworm Dilong (Lumbricus) and other medicinal insects such as Jiangcan (Bombyx) represent the natural precursor to the extract Lumbrokinase, which some naturopaths and MDs now use for the specific purpose of breaking down biofilm. These herbs specifically address the problem of bio-film. The Chinese have used this approach for eons: use a worm to address another “worm” in your body, an almost homeopathic principle.

Finally, there are the herbs with a direct anti- parasitic effect, lead by Qinghao. There are lots of other anti-Gu and anti-malarial herbs in this category. Some are well known like Xuanshen (Scrofularia) and Tufuling (Smilax) and Huzhang (Polygonatum cuspidatum). Others are completely forgotten like Xuchangxing (Cynanchum) and Guijianyu (Euonymus alatus). In Chinese, the latter’s name literally means “the arrow that kills demons.” There is a long list of herbs in this category, and it is from here that most Western Lyme prescriptions are culled.

The next important category consists of herbs that stabilize the immune system to treat and prevent autoimmune complications. Spirochetes are recognized by our immune system as a particularly tricky invader; consequently, it often goes into overdrive in response to the presence of these pathogens. Among the Chinese organ networks, it is the Spleen that is most often implicated in autoimmune processes. Some Chinese medicine texts, therefore, describe the Spleen as “the mother of all wind.” On the Chinese organ clock, for instance, the Spleen is located in the position of the 4th lunar month, which used to be called the “wind corner” of the zodiac. It is important to point out that herbs affecting the Spleen were not exclusively thought of as qi tonics such as ginseng and astragalus. Ancient texts also relate certain herbs that clear wind and blood heat to the Spleen. Three herbs that I find particularly important in this context are the classic food items Wanggua (Snake gourd), Jicai (Shepherd’s purse) and Kucai (Hare’s lettuce). These herbs are never used as ingredients in Chinese herbal formulas anymore, but I find them exceedingly useful and have begun to import them as part of the Classical Pearl powdered extract series, as well.

The last, and perhaps most important, category in this anti-Lyme material medica is composed of warming and strongly anti-parasitic herbs from the aconite family. During the last three years, when I synthesized the knowledge transmitted in the classic Gu texts into a general approach to Lyme, I concluded that the use of aconite is indispensible for most Brain Gu patients, especially in the middle and later stages of treatment. I have found different varietals of aconite to be integral elements of a long- term treatment plan for Lyme disease and other forms of nervous system inflammation, specifically Fuzi (lateral offshoots of Aconitum carmichaelii root) and Chuanwu (taproot root of same plant).

At the beginning of this discussion, I emphasized how important I believe it is to work WITH the life force rather than against it—recommending, in essence, a sustained support of the body’s yang qi. The brighter the body’s alarm lights are turned on— and few pathogens activate emotional and physical symptoms like Lyme spirochetes—the greater the stress and the gradual depletion of the body’s yang forces. At the beginning of therapy, Lyme patients may exhibit superficial signs of heat, such as rapid pulses, rashes, feverish sensations, and nightsweats, yet these most often mask an underlying condition of coldness and exhaustion. Once these symptoms disappear with the moderate to slightly cooling approach outlined in the design of Lightning Pearls, Thunder Pearls, Ease Pearls, and Dragon Pearls, the more the body will be comforted by the use of formulas that warm the yang and consolidate the body’s mingmen (gate of life) “battery.”

The most prominent symptom of shen disturbance in Lyme patients is anxiety and insomnia. Anxiety, from a classical Chinese perspective, represents yang qi rushing out of dantian storage because the body is in a constant state of alarm. To treat this phenomenon, we need to draw this energy back into the box. If a Lyme patient has been suspended in a heightened state of stress for years or even decades, then (from a Western perspective) the system becomes traumatized and the adrenals burnt out. From a Chinese perspective, the reserves in the lower dantian are empty and cold, while the remaining energy is floating at the surface. As the teachings of the Fire Spirit School of Chinese herbalism show, it is the herbs Aconite, Sharen (Amomum) and Huangbai (Phellodendron bark) that are best for drawing flaring yang qi back into the dantian. The overall process of “recharging” the body’s vital fire without tonifying the parasites is a must, especially if our therapeutic goals include a future in which the patient is healthy enough to fight off the remaining pathogens on his/her own.

Two important things to remember when prescribing aconite are: 1) Exclusively use genuine aconite from Jiangyou in Sichuan that has been grown and processed in accordance with traditional specifications (to the best of my knowledge, Classical Pearls is presently the only company that supplies this quality of aconite in the West in powder extract form); 2) For purposes of alchemical stability, it is best to combine aconite with ginger (Shengjiang, Ganjiang, or Paojiang) and licorice (Gancao). (i)

When designing a custom Brain Gu formula, I typically use 12-15 herbs, with an average of 1-3 herbs from each of these categories. I find it important to consistently rotate at least one herb in each category every 4-6 weeks. In this way, you can stay ahead of the adaptive ability of the parasite, and avoid triggering allergic responses from your own body. This procedure can include minor changes, such as changing Guizhi to Rougui, or Fuzi to Chuanwu within a category; or medium changes, which involve changing at least one herb in each category; or major changes, which result in a change of the entire base formula. Dosages vary: generally, I use between 12-18g of powder extracts per day (equivalent to 60-90g of decocted crude herbs per day), but in certain cases of extreme sensitivity I start with a much smaller dosage (2-6g per day), otherwise the super-sensitive types may be overwhelmed by so-called Herxheimer reactions—a common phenomenon in Lyme patients, when the spirochetes are still strong enough to react to a newly introduced treatment.

Most often I combine custom formulas with some of the Classical Pearls family of patents, many of which I created for the specific purpose of treating patients suffering from chronic inflammatory conditions. The herbal powder extract in one Classical Pearls capsule is equivalent to a decoction of 5g of crude herbs. When only prescribing Classical Pearls formulas, I typically use about 9-18 capsules per day for the average Lyme patient (most often combining 2-3 different Classical Pearls formulas), and 2-6 capsules for the super-sensitive types (at the beginning).

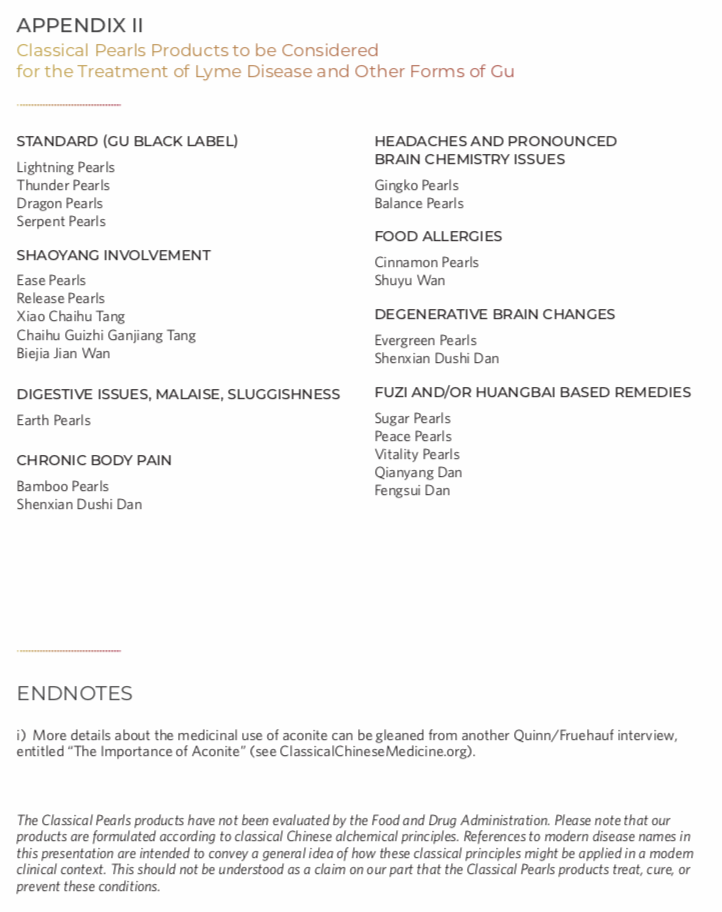

The Classical Pearls series of patent remedies I created has three primary goals, all of which are relevant for the treatment of Lyme disease: 1) to make available classical treatment methods that treat modern diseases at the root, with strict adherence to the highest standards of purity and safety; 2) to uphold the vital principle of “supporting yang” in all formulas—working with the life force rather than against it; 3) to create modular solutions for chronic inflammatory syndromes, which so far have not been readily recognized as a common disorder by the Chinese medicine community. Of the 58 Classical Pearl remedies presently in production, about half can play a potential role for the treatment of Gu syndrome in general and Lyme disease in particular.

QUINN: Thank you for talking with us today. We appreciate your time. I hope this interview will be of benefit for those who listen to it or read the transcript.

BE SURE TO VIEW THE SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL ON PAGES 8-9.